This article was first published in Radar magazine in March, 2008

Backed by an army of punked-out teens, cult Russian novelist Eduard Limonov dedicated himself to taking on Vladimir Putin. Will death threats and nutty supermodels derail his democratic revolution?

It’s 6 a.m. on a Saturday morning in June when I arrive at the home of Russian opposition leader Eduard Limonov. It’s shaping up to be another grimy, humid summer day in Moscow. We need to get an early start if we’re going to make our flight to St. Petersburg, where Garry Kasparov, the chess legend who recently joined the political fray, and Limonov, Russia’s most infamous literary celebrity, are planning to lead a protest against the country’s autocratic president, Vladimir Putin. Together the two head up a ragtag coalition of anti-Kremlin parties known as Other Russia.

The last two times Limonov went to St. Petersburg, things got ugly. In April, an Other Russia protest ended with cops attacking throngs of marchers while Putin’s paramilitary goons hunted down and detained Limonov and then brutally stomped his bodyguards. Six weeks before that, another anti-Kremlin rally in Russia’s “second city” devolved into truncheon thrashings and unlawful arrests. Limonov was taken into custody in an operation that looked like something out of the Peloponnesian War: Black-clad Kremlin shock troops charged in formation into a phalanx of Limonov supporters, mercilessly beating anyone in their path until they reached their target.

Limonov buzzes me into his building. I climb up a couple flights of stairs, and then wait while he looks out at me through the peephole of his black steel door. We’ve known each other for more than a decade, during which he has been a controversial and high-profile columnist for the English-language alternative newspaper I run in Moscow, the eXile. I’m no threat, but Limonov is one of the most marked men in Russia today, and if any of his enemies ever decide to whack him, chances are they’ll do it right here. A wide array of politicians, journalists, and businessmen have been gunned down while entering or leaving their apartments or offices—including the high-profile cases of investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya and Forbes Russia editor Paul Klebnikov. The only time I’ve ever seen Limonov betray something like hunted mammalian unease is when he enters the invisible red zone outside his front door—which is why he almost never travels without bodyguards.

He unlocks a series of dead bolts and opens the door. “Come in,” he says, then quickly shuts it behind me. His muscle hasn’t arrived yet.

The writer, now 65, is sharp-featured, lean, and energetic. With his flamboyant haircut and Trotsky-like goatee, he looks like an aging Marxist rock star. Since returning to Russia in 1992, after living in exile in France and the United States for nearly two decades, he has been pursuing his lifelong fascination with revolutionary politics. In 1993, he founded the National Bolshevik Party, which encompasses a strange and evolving mixture of nationalism, left-wing economics, punk-rock aesthetics, and a constant desire to shock. Politics has always been a blood sport in Russia, and ever since he started the party, Limonov has lived under threat. He spent two years in jail during Putin’s first term in office.

But things didn’t get really bad until a little over two years ago, when a gang of youths went after his followers with baseball bats, cracking skulls, ribs, and limbs. Some of the perpetrators later caught by local cops were wearing T-shirts from the Kremlin youth organization Nashi, or “Ours.”

A few of Limonov’s more vocal supporters in the Russian provinces have died under mysterious, violent circumstances. Not so long ago, a well-connected friend warned me to stay away from him if I didn’t want something bad to happen to me. (I decided to take my chances.)

This year, the writer has received his two most serious death threats to date. One was passed on by a powerful Duma deputy closely tied to the FSB, the successor agency to the KGB and the beast that spawned Putin. The other came from former FSB operative Andrei Lugovoi, Scotland Yard’s chief suspect in the high-profile polonium poisoning of Putin foe Alexander Litvinenko in 2006. At a press conference last spring in Moscow, Lugovoi—who, like a Russian O.J., has been basking in his guilty-‘n’-gettin’-away-with-it fame—told reporters, “I think something is being prepared for [Limonov].” Lugovoi then claimed that the murder plot was a clever ruse by exiled billionaire oligarch Boris Berezovsky, intended to discredit President Putin.

The threat simply added to the general sense in Russia that anyone who opposes Putin should expect to be the target of violence or persecution. At this point the serious competition has been jailed, exiled, or otherwise brought to heel, and Putin’s hold on political power appears to be absolute. While he’s obliged by Russian law to step down in March after his second term ends, Putin has found a way to circumvent his term limit and retain power. He anointed a successor, Dmitry Medvedev, as his proxy in the country’s upcoming presidential elections. Now Putin will slide into the prime minister’s chair with Medvedev as his executive puppet. “He clearly will be supreme leader, maybe leader for life,” declared a Time editor shortly after the magazine named Putin Person of the Year for 2007. The only glimmer of popular opposition against the increasingly authoritarian regime is a handful of eccentric radicals like Limonov and Kasparov. That they’re still around suggests the Kremlin considers them a safer brand of adversary than Berezovsky or Yukos oil oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, formerly one of the world’s richest men, who today sits in a Siberian prison on various charges, including tax evasion.

The Kremlin may be right about Kasparov—after all, the former world chess champion has been relentlessly building a future for himself and his family (including his American-born child) in the United States, where a series of speaking gigs have helped make him the biggest stateside Russian sensation since Mikhail Gorbachev. It’s Limonov who is the real wildcard. His organization provides the bodies in the Other Russia coalition. And the last time he was jailed for his political activities, he emerged stronger and more determined than ever in his opposition to Putin.

As we stand in the kitchen and wait for his bodyguards to arrive, Limonov runs through the day’s itinerary: He, Kasparov, and their respective entourages are supposed to convene at Mayakovsky Square and then caravan to Sheremetyevo airport to fly to St. Petersburg. The two opposition leaders always try to travel together to rallies so that one or the other isn’t individually detained—appearing in tandem at Other Russia events is key to keeping the coalition energized and unified. Everywhere they go, they are trailed by intelligence agents, who no longer even bother to be discreet.

At an opposition protest in the capital last spring, security forces managed to physically separate the two men, which created disarray among the protesters. In the melee, Kasparov was detained and thrown in jail while Limonov slipped away and did an end-run around the police with an all-night drive on back roads, arriving in St. Petersburg in time for the next rally, where he was then also detained. (Unexpectedly, though, having Limonov held in St. Petersburg and Kasparov in Moscow became a major publicity boon for Other Russia.)

“What do you think the authorities have planned for you today?” I ask him as he paces around his modest kitchen. The room is austere and clean, with simple Brezhnev-era furnishings and an old bathtub just a few feet from the stove. A wooden plank laid widthwise across it holds his soap, shampoo, and toothbrush. It seems to reflect not only Limonov’s contempt for middle-class consumerism and clutter, but also his Spartan, disciplined mentality, which has kept him focused on his impossible, lifelong dream: to lead a political revolution in Russia. Only a small-minded sucker would waste his money on some built-in IKEA kitchen—junk for “the goat herd,” as Limonov calls the bourgeoisie in an early autobiographical novel, Memoir of a Russian Punk.

“I have no idea what will happen today,” he replies. “Anyway, I don’t give a shit. It’s a waste of time trying to guess what the Kremlin has planned for us. We have to worry about our own plans for ourselves.” The very notion that he should expend energy guessing what his Kremlin foes are thinking irritates Limonov on some basic level. It implies subservience. “They may do what they did a few weeks ago, this ‘soft authoritarianism’ bullshit, and not let us go to Petersburg.”

Three weeks earlier, Kasparov, Limonov, their aides, and about a dozen Western journalists, including myself, were detained at Sheremetyevo. We were supposed to fly to Samara for a protest rally, but the woman at the Aeroflot check-in desk claimed that everyone’s tickets were possibly counterfeit, so we all had to stick around for questioning. Kasparov pounced on her, relentlessly dissecting her claim. A border guard relieved her, but the poor bastard quickly regretted it: Kasparov was immediately on him, too—something like that face-sucking creature in Alien. The chess champion scoffed, threw up his hands, and mocked the man. “You’re not serious! You can’t be! It’s shameful, a parody, theater of the absurd! You’re breaking the law! Do you realize that you, a law enforcement official, are breaking your own laws? It’s just unbelievable!” Kasparov then turned to a captain in Russia’s Ministry of the Interior who had joined the fray: “Bring my passport back to me. You have no right! Bring me my passport!”

Limonov, meanwhile, withdrew to the other side of the airport lobby with his bodyguards, where they squatted Central Asian style, looking around with bored and contemptuous expressions. The writer and his crew were dressed in black, while Kasparov wore dowdy blue jeans, a baseball cap, and a tan, Eddie Bauer–style windbreaker. He took a series of cell phone calls from the media and continued his arguments with the authorities, without missing a beat.

“You don’t want to bitch everyone out, the way Garry is?” I asked, as Kasparov demanded to see the identification of one of the agents, and then let out a savage laugh.

“You know, I have 13 years’ political experience,” Limonov said, smiling. “I don’t give a fuck about these schmucks. I don’t get so excited about little things as I used to. I’ll answer their questions, yes, yes, and then get the hell out of here. This isn’t my style.”

We were detained until the last plane for Samara took off, ensuring that Kasparov and Limonov would miss the protest rally. Putin was in Samara that day, hosting German chancellor Angela Merkel. It was supposed to be a routine photo op, but when news hit that the Other Russia leaders had been barred from coming, Merkel went about as ballistic as a dour middle-age German bureaucrat possibly can. At their joint news conference, she scolded Putin: “I can understand if you arrest people throwing stones or threatening the right of the state to enforce order … But it is altogether a different thing if you hold people up on the way to a demonstration.”

Putin didn’t fancy being lectured and struck back with a list of countercomplaints, leading the BBC to conclude that Russian–EU relations had “reached a new low.”

The discord was another publicity coup for the opposition. When we finally left the airport, a mob of mostly foreign reporters, television crews, and photographers swarmed Kasparov, while Limonov slipped away with his bodyguards. “Garry has the patience for their idiotic questions, which is good for me,” he said, an inkling of a smile on his face. “Anyway, the Western journalists are mostly afraid of me.”

Before his career in politics forced him to adopt disciplined habits, Limonov led a wild, decadent existence—much of which became the raw material for his early novels and poems. He hung out with rock icons like Marky Ramone and punk legend Richard Hell, and the last three of his four wives have been stars in their own right.

“I think this life he lives now, spending so much time locked inside his apartment or in meetings, causes Limonov some pain,” says Thierry Marignac, a French author who was one of Limonov’s closest friends while Limonov was living in exile in Paris in the ’80s. “He was very social and he liked partying. He saw himself as a kind of Elvis Presley of poetry.”

Limonov wrote the first sexually explicit, brutally amoral novels that the Russian language had ever seen. His debut effort, It’s Me, Eddie—which has been compared to the work of Henry Miller by some critics—was banned by the Soviet government but has sold more than a million copies in Russia since it was published there. The book chronicled his breakup with his wife Elena, a fashion model who was also a flamboyant luminary in Moscow’s beau monde. They moved to New York in 1975, where she ditched him for an Italian count. Limonov went on welfare, drank prodigiously, and—if his autobiographical novel is to be believed—had sex with anyone he could, sampling the gamut from beautiful young women to scabrous homeless guys. He poured his bitterness against Americans into the book: “I scorn you because you lead dull lives, sell yourselves into the slavery of work, because of your vulgar plaid pants, because you make money and have never seen the world. You’re shit!” He also raged against the West’s propaganda about its freedoms: “They’ve got no freedom here, just try to say anything bold at work … You’re out on your ear.”

Limonov crawled out of obscurity after his novels became celebrated in France in the years that followed. Leveraging his return to fame, he married another larger-than-life Russian model, Natalya Medvedeva, a strikingly tall, sharp-boned woman built like a praying mantis. (If you’ve seen the cover of the first Cars album, then you’ve seen Natalya Medvedeva; she also posed for Playboy.) Together, they moved to Paris and had a famously cruel, public relationship, replete with affairs and scandal.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the couple moved home so Limonov could pursue his dream of getting involved in Russian politics. Limonov’s vision for his life was something on the order of a modern Lord Byron: a writer who undertakes political projects so grand and strange that they would seem to have sprung from the pages of a novel (or an epic poem, in the case of Byron, who led a rebel army and became a national hero in the Greek War of Independence). But Medvedeva’s hard-partying lifestyle didn’t jibe with his new ambitions, and they split up in 1994. She hooked up with a famous metal guitarist and later died of an apparent drug overdose, while Limonov began a series of affairs with ever-younger fans of his bad-boy politics and art.

The writer’s youthful paramours in those years often shaved their heads as a show of loyalty to the dark prince of Russia’s underground. Before he was jailed by Putin in 2001—convicted on a weapons charge related to a bizarre scheme to raise a private army and invade Kazakhstan—his last girlfriend had been a feral teenage punk named Nastya. She was bald and uncontrollable and enjoyed vandalizing his apartment, which was a source of great amusement to him. But after his release from prison in 2003 transformed Limonov into an opposition icon, he lost interest in adolescent lovers.

In 2006, at age 63, he married his fourth wife, Ekaterina Volkova, then a 31-year-old pinup model and Russian television star who bears a much-noted resemblance to Angelina Jolie. She shaved her head and bore him his first child—a son.

She is now pregnant again, a development that seems to have saved the couple’s marriage. “I got sick of everything,” Limonov tells me, recalling a recent fight with Volkova that ended with a short separation. “I threw my vodka glass at her, and it almost hit my mother-in-law in the head. Anyway, a couple of weeks later, I find out that she is pregnant with my second child, so that brought us back together again.”

In late September, the Other Russia coalition holds their national convention in a renovated theater hall in Izmailovsky Park, on Moscow’s eastern fringe, to nominate a presidential candidate for the upcoming election. Their choice will stand zero chance of winning, but will be symbolically important in flying the flag of opposition to the Kremlin’s increasingly authoritarian rule. Delegates come from all over the country and are an eclectic mix: Kasparov-allied liberal intelligentsia mingling with hardcore nationalists, broke war veterans, and—most of all—droves of Limonov’s punk-rock kids. Though Kasparov is eventually named the presidential candidate, he actually has relatively few supporters in the hall. Instead, his nomination comes as the result of an agreement worked out with Limonov, whose followers could swing the vote in any direction.

Kasparov, whose name is far better known in the West than Limonov’s, hit international democracy-activist superstardom this year. Not only is he the neocons’ Nelson Mandela (the Wall Street Journal‘s nutty op-ed page has named him contributing editor), but American liberals love him for his wit and charm, and because he criticized the Bush administration for backtracking on promoting democracy in Russia.

But in reality, Limonov provides most of the organizational force behind Other Russia: His 15,000 or so loyalists consist largely of young artists, intellectuals, skinheads, anarchists, and other outsiders. In the past, the group incorporated fascist and ultranationalist elements into both its platform and presentation, and embraced some questionable allies—one of Limonov’s most despicable episodes came during the Balkan conflict when he fired automatic weapons down on the city of Sarajevo from a mountain encampment shared with accused Serb war criminal Radovan Karadzic. But the party now hews to a straight leftist political line on most issues, playing down its aggressively nationalistic stances. Putin’s cynical use of nationalist rhetoric to manipulate public sentiment was partly responsible for the shift. “We live in a truly despotic regime,” Limonov says. “This government is cruel to the poor and the vulnerable. Its only ideology is nationalism. Our left-wing views are much closer to those of the masses. If we were allowed to operate in a free society, I am sure that we would become the most popular party.”

But what seems to animate Limonov’s legions of loyal followers most is his philosophy of “Russian Maximalism”: going for broke to free oneself and one’s nation from all forms of oppression. For the young punks, this means raging not only at the Kremlin, but also at the out-of-control consumerism that has taken root in this newly rich nation. You can see their fanatical enthusiasm in their suicidal political stunts, like the time they egged a prime minister while he was voting in an election, or when they took over the Health Ministry office and trashed portraits of Putin until FSB commandos arrived and kicked the shit out of them. Hundreds of them have seen the inside of Russia’s jails.

Limonov’s opposition to Putin is not new. When Putin took power in late 1999, the writer became one of his earliest and fiercest critics. “We were practically the only group to oppose him from the start,” he says. “Why would I support this KGB schmuck who weaseled his way into power? It was obvious for us, but at the time, many liberals supported him.” Within two years Limonov was in jail and being vilified on state television. The state’s case grew out of a series of unbylined articles in Limonov’s party newspaper advocating occupation of northern Kazakhstan with a private army to set up an ultranationalist Russian state.

In the summer of 2003, he was unexpectedly paroled, thanks to the intervention of some powerful friends in parliament. Shortly after his release, my mobile phone rang: “Mark! It’s Eduard! I’m out of that fucking prison and back in Moscow. So let’s meet! It’s been a long time!” He was as cheerful as ever and full of fighting energy—as if he hadn’t been stuck inside one of Russia’s infamous overcrowded, tuberculosis-infested cells for two and a half years. During his incarceration, he had written eight books.

His release was an important moment for Russia’s underground opposition. He’d fought the czar and won. The National Bolshevik Party’s ranks suddenly swelled with thousands of young followers, across Russia’s 11 time zones. To them, Limonov was a real-life Fight Club rebel, always ready to put everything on the line. Violence and incarceration seemed only to fuel his sense of purpose.

But this morning, in June, bound for St. Petersburg, everyone is nervous as we climb into a black Volga and head off toward Mayakovsky Square. Limonov is sandwiched between two hefty bodyguards in the backseat, while I ride shotgun. At 7 a.m., we link up with Kasparov and his entourage, who are rolling in expensive white SUVs. The traffic looks bad and the chess champ wonders aloud whether it’s a sign—or even a Kremlin plot to make us miss the plane. But there will be nothing like that. This time, I’m the only one detained, while the two leaders of Other Russia are waved onto the airplane with their bodyguards, a film crew from 60 Minutes trailing behind. (They’re working on a profile of Kasparov, which in its final form will not even mention Limonov.) In the end, I’m allowed to join them just minutes before the plane takes off.

The protest in St. Petersburg goes off without incident. When the speeches and chants are finished, there’s a palpable sense of letdown. Democracy protests are supposed to lead to evermore dramatic confrontations with authorities—culminating either in martial law or popular revolution. But in Russia’s case, the dynamics have already changed too much, and that narrative simply doesn’t fit.

Kasparov’s rhetoric about a Ronald Reagan–inspired liberal revolution seems downright silly in a nation where Putin enjoys more than 70 percent approval and anti-Americanism and anti-liberalism run deep. His candidacy for president will fall apart in December 2007, when the Kremlin requires that Other Russia hold an officially sanctioned nomination in a large public event hall—an impossible requirement since the owners of every such facility in Moscow are too frightened to rent to the party.

Limonov, by contrast, has always shown his mettle as a political activist by quickly adjusting to real-world circumstances.

Over the course of several conversations in November and December, he describes to me an incredibly audacious and media-savvy scheme to expose Putin and Russia’s subordinate parliament. It’s the kind of stunt that will make the capillaries in Putin’s eyes pop in anger and give a jolt of energy to the opposition movement. But he makes me promise not to disclose any details, fearing what the Kremlin will do to stop him. Kasparov’s press spokesperson slips up and gives a hint while her boss is still in jail in November, saying that since Putin’s legislature won’t pass democratic laws, a united opposition front will pass them instead.

It’s not clear if Putin is even aware of this mysterious plan, but—coincidence or not—a new crackdown seems to be underway with the arrival of winter. Shortly before a major Other Russia protest in Moscow on November 24, a 22-year-old activist is bludgeoned to death near his home. Shortly before, he had called another opposition activist from his mobile phone and reported that he was being followed by secret police. At the protest itself, Kasparov is arrested and held for five days. (“I wouldn’t recommend Russian jails to anyone,” he tells me darkly when I reach him after his release.) Meanwhile, Limonov is the target of a new court order. A criminal case seems to be in the works, alleging that the writer continues to operate the now-banned National Bolsheviks.

I ask Limonov what he thinks the Kremlin’s reaction will be when he goes public with this mysterious and provocative new plan. “I don’t think they’ll be too pleased,” he says, not betraying much emotion. “Maybe they won’t kill me, maybe they’ll just arrest me. Anyway, we’ll find out soon.”

This article was first published in Radar magazine in March, 2008

Mark Ames is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast with Gary Brecher. Subscribe here.

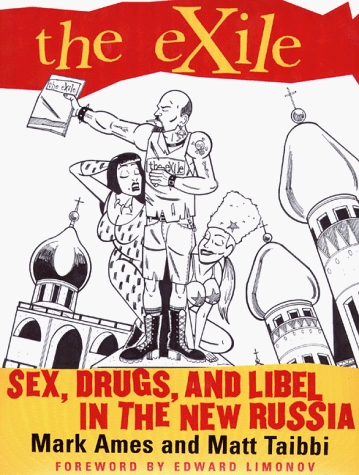

Still like to know more? The eXile: Sex, Drugs and Libel in the New Russia co-authored by Mark Ames and Matt Taibbi (Grove).